Edible Mushrooms of the Pacific Northwest

Welcome to the Pacific Northwest, a captivating expanse that stretches across parts of British Columbia, Washington, Idaho, and Oregon. While many marvel at its lush forests, rugged coastlines, and majestic mountains, it’s the region’s incredible variety of mushrooms that catches the eye of foragers and nature enthusiasts alike. Thanks to the area’s consistent moisture and incredibly diverse forests, a plethora of mushroom species call this place home.

Imagine walking through these woods and spotting golden chanterelles emerging from a blanket of moss or discovering hundreds of morels nestled among warm pine needles. The unique blend of climate, landscape, and local ecosystems turns the Pacific Northwest into a true treasure trove for those passionate about the fascinating world of fungi.

The Ecology of Mushrooms

Understanding Mushroom Ecology: An Introductory Guide

Mushrooms, often recognized as the conspicuous fruiting segments of certain fungi, are pivotal components in the intricate ecological network of our planet.

Preferred Habitats: Mushrooms have a diverse range of homes. While many are nestled within thick forests, blooming meadows, decaying wood, or fertile soils, their preferences can vary. Some favor the moist and shaded environs of deep woods, while others are adept at flourishing in more exposed or dry locales.

Purpose of Mushrooms: Mushrooms are the reproductive fruitbodies of fungi. Mushrooms are just one part of the overall fungus, most of which may be hidden from view.

Just as an apple tree will produce apples for reproduction, some fungi produce mushrooms as part of their reproductive cycle.

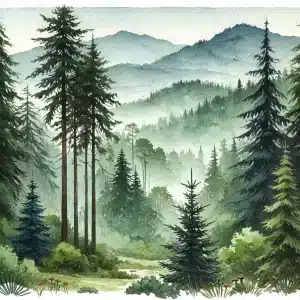

Growth Dynamics: Beneath the surface, the predominant part of a fungus exists as ‘mycelium’—a dense web of hair-like entities. When external conditions align optimally, factoring in elements like the right temperature, adequate moisture, and nutrient abundance, this mycelium converges to form the mushroom. Subsequently, this formation pushes through to the surface, whether that’s soil or wood, revealing itself to the world.

The mushroom grows rapidly, absorbing water and nutrients from its surroundings. Once mature, it releases its spores, either carried away by the wind, water, or animals, ensuring the continuation of its life cycle.

Some mushrooms are nature’s recyclers. They break down organic matter, converting it into nutrients that enrich the soil and support other forms of life. They also create the internet of the forest by establishing a unique connection with live trees and plants. These important roles underscore their significance in maintaining a balanced, resiliant, and healthy ecosystem.

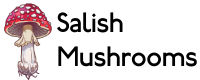

Popular Edible Mushrooms in the Pacific Northwest

In our exploration of mushrooms native to Washington, Oregon, and British Columbia, we’ll begin with some of the most favored varieties for foragers. These particular mushrooms stand out not only for their abundance and rich flavor but also for their distinguishable features, which make them easier to identify compared to other edible species.

We will look at Chanterelles, Morels, King Boletes, and Bear’s Head – four beginner-friendly Pacific Northwest mushrooms beloved by chefs and foragers alike.

Chanterelle

Cantharellus spp (read more)

One of the most sought-after delicacies of the Pacific Northwest’s forests is the Chanterelle mushroom. Recognizable by its unique appearance, the Chanterelle is distinguished by the rounded veins on the underside of its cap, a characteristic that sets it apart from many other mushroom species. Its meaty flesh is not only a treat for the palate, golden flesh a treat for the eyes, and sometime fruity scent a treat for the nose.

Chanterelles have a symbiotic relationship with the region’s conifer trees. They predominantly grow in the soil in association with Douglas fir and western hemlock, intertwining their mycelial networks with the tree roots. While these mushrooms can be spotted from summer through winter, they particularly flourish with the onset of the autumn rains. For those wandering through the Pacific Northwest’s dense forests, the sight of these golden treasures amidst the undergrowth is a testament to the region’s rich ecosystem living within the soil.

Basics of Chanterelle Identification

King Bolete

Boletus edulis group (read more)

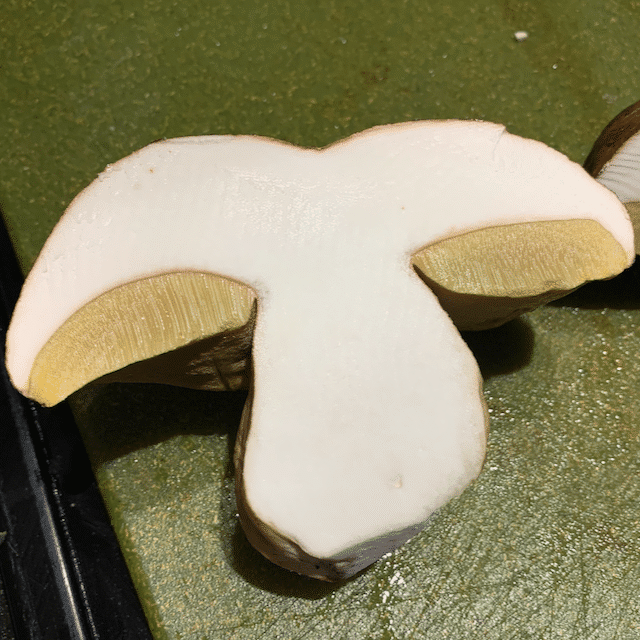

The King Bolete is a mushroom revered not only in this region but across vast stretches of the northern hemisphere. These and other bolete-like mushrooms are noted for their spongy pores located on the underside of their caps, a distinct departure from the typical gilled structure seen in many other mushrooms.

Their universal appeal and distribution have earned them a medley of names across different cultures. Whether you call it ‘porcini’ in Italy, ‘cep’ in France, ‘penny bun’ in England, or ‘Eekhoorntjesbrood’ (literally translating to ‘squirrel bread’) in the Netherlands, the mushroom remains a favorite for both its culinary and aesthetic appeal.

You can learn more about the region’s diverse group of boletes here

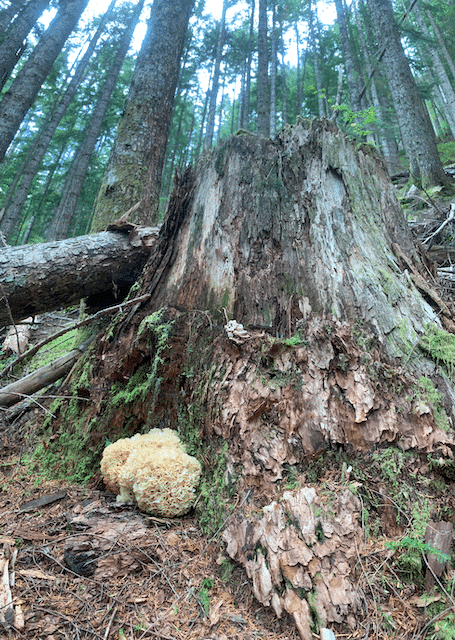

Bear’s Head and other Hericium species

Hericium spp (read more)

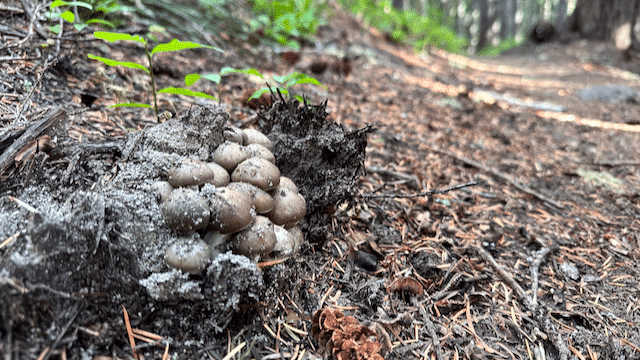

Bear’s Head, a fascinating member of the Hericium genus, stands out as a true spectacle in the world of fungi. They adopt a distinctive pom-pom like appearance, closely resembling their namesake or even coral from the deep seas. One of the most striking features of the Bear’s Head and its Hericium cousins is the myriad of small spines that dangle downward or project whimsically in all directions, giving it an almost ethereal appearance.

As decomposers, these mushrooms have an exclusive affinity for wood, making them a frequent sight on fallen logs or decaying tree trunks. When fresh, they dazzle with an ivory white hue.

Beyond their captivating appearance, the Bear’s Head offers a culinary experience as well. Their mild flavor is complemented by a unique, almost crab-like texture, making them a favored ingredient in various dishes.

In a forest replete with wonders, Bear’s Head and other Hericium species offer a mesmerizing blend of visual charm and culinary delight.

Read more about Bear’s Head and other Hericium species

Growing Lion’s Mane (Hericium erinaceus)

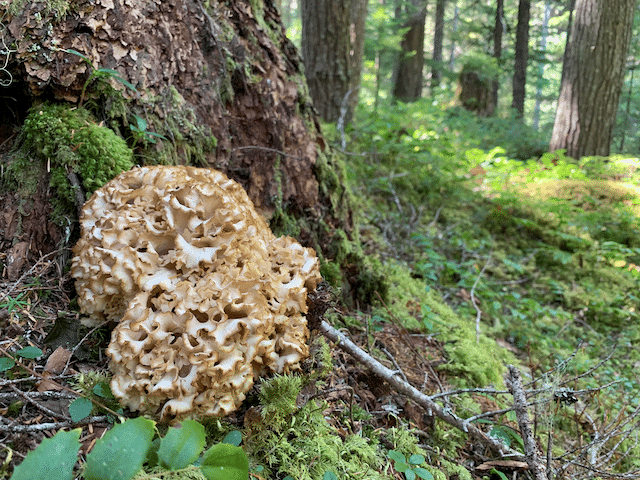

Morel

Morchella spp (read more)

Emerging with the thaw of winter and the melting of mountain snows, morels signal the arrival of spring in the Pacific Northwest. As one of the most coveted wild mushrooms, morels are instantly recognizable by their distinct pocketed and honeycombed appearance, setting them apart from other fungi.

The world of morels is diverse, encompassing a variety of species, each with its own set of habitat preferences. While some morels demonstrate an affinity for wood chips that are a year old, lending themselves to urban and suburban foraging, others are closely tied to nature’s cycles of destruction and renewal, sprouting robustly in areas that witnessed forest fires the previous year. Still, other species favor the dampness of river bottoms or the higher elevations amongst living trees in the mountains.

Such variety in habitat requirements not only makes the hunt for morels an exciting challenge for foragers but also showcases the adaptability and resilience of this fascinating fungal genus. Whether they’re found in burn scars, riverine landscapes, or mountainous terrains, morels remain a cherished springtime treat for those lucky enough to spot them.

Lesser Known Delicacies

Hedgehog

Hydnum spp (read more)

Traversing the diverse fungal landscape of Washington, Oregon, and British Columbia, one is bound to come across the delightful hedgehog mushroom. Renowned as one of the most delectable edibles in the region, these mushrooms stand out due to the tiny, spine-like projections on the underside of their caps – a feature that inspired their quirky name.

Unlike the typical gill or pore structures seen in many mushrooms, the hedgehog’s unique spines provide a fascinating texture contrast. This, combined with their naturally crunchy texture, makes them a favorite among culinary enthusiasts. Often playing hide and seek, these mushrooms are commonly nestled under thick moss blankets on the forest floor, waiting to be discovered by keen-eyed foragers.

Their presence isn’t limited to just one part of the Pacific Northwest. These mushrooms proudly stake their claim from the high elevations of the Cascades, sweeping down to the misty coastal forests, and spanning a vast range from Alaska all the way to the Bay Area.

Read more about hedgehog mushrooms

Lobster Mushroom

Hypomyces lactifluorum on Russula/Lactarius spp (read more)

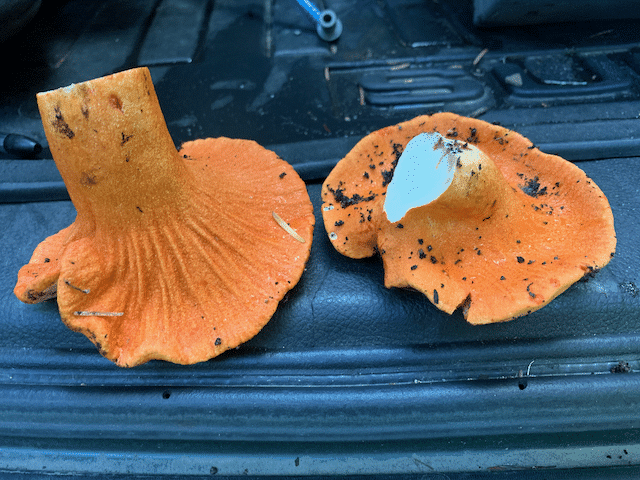

The lobster mushroom is not just a single entity but a stunning result of one fungus overtaking another. Vibrant in color and robust in flavor, these mushrooms capture the essence of their namesake – both in their reddish-orange hue reminiscent of a cooked lobster and their firm, seafood-like texture.

What makes lobster mushrooms especially intriguing is their origin. They are the product of the parasitic fungus, Hypomyces lactifluorum, infecting certain species of mushrooms, notably those in the Russula and Lactarius genera. This parasitic takeover results in the transformation of the host mushroom, both in color and structure, leading to the distinctive appearance and characteristics of the lobster mushroom.

Their robust flavor and meaty texture make them a favorite among chefs, lending well to a variety of dishes where they often stand out both as a visual centerpiece and a taste sensation. Found during the late summer and fall, foragers prize these mushrooms not just for their culinary value but also for the unique story they tell about the complex interactions within the fungal world.

Read more about lobster mushrooms

Cauliflower

Sparassis spp (read more)

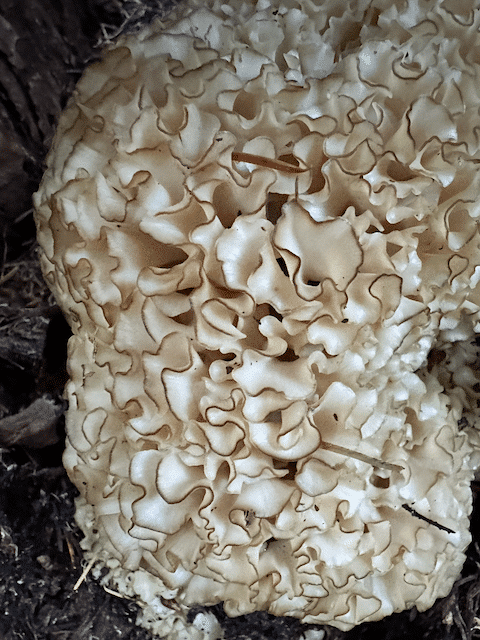

The maze-like, layered appearance of Sparassis radicata not only makes it a visual delight but also offers a unique texture when used in culinary preparations. Its branching, leafy, egg-noodle like lobes are tender and have a subtle flavor, making them a cherished find for chefs and foragers alike. Sparassis species are also know for a slightly spicy fragrance providing an olfactory delight in the forest.

Found at the base of conifer trees, this mushroom lives as a parasite on the roots of the tree. When harvesting these massive mushrooms, a forager will note a long brainstem extending deep into the soil below. Cut the cauliflower mushroom away from this protrusion at soil level to reduce the impact to the soil and improve the chances of another mushroom growing back in its place.

For those lucky enough to stumble upon the Sparassis radicata during their woodland adventures, it serves as a reminder of the incredible diversity and intricate beauty of the fungal kingdom hidden amidst the forest floor.

Read more about cauliflower mushrooms

Chicken of the Woods

Laetiporus spp (read more)

Laetiporus conifericola, commonly referred to as “chicken of the woods,” is hard to miss. With its flamboyant, bright orange hue, this mushroom serves as a striking complement to the more subdued green tones of the forest floor.

A hallmark of this species is its overlapping shelves of orange sprouting from wood, a testament to its role in the decomposition of fallen or decaying trees. The underside has incredibly small, pale-to-creamy pores,, creating a stunning contrast to its more vividly toned top layer. As the mushroom ages, its texture undergoes a notable transformation, evolving from tender to a more chalky consistency.

Yet, despite its visual allure and firm texture, the chicken of the woods comes with a word of caution. It’s not universally tolerated. Some have reported gastrointestinal distress, including cramping and diarrhea. It’s advised to approach this mushroom with care. Culinary experts often recommend cooking it low and slow, a method believed to reduce the likelihood of adverse reactions.

Easy identification and conspicuous growth habit make chicken of the woods one of the key edible mushrooms in the Pacific Northwest

Pacific Northwest Foraging

Online Course

– Key Features

– Look-alikes

– Habitat

– Seasonality